Click here for a Workbook to go along with this lesson.

The following videos are available to reinforce the concepts taught in this lesson:

Sentence Practice, Dictation, Lesson Recap

This lesson is also available in Русский, Français, Português, Nederlands, Español, Magyar and العربية

Jump to:

Explanation of 좋다/싫다 to 좋아하다/싫어하다

Subject – Object – Adjective Form

Korean Word: 들다

Korean Compound Verbs

Different/Similar/Same in Korean (다르다/비슷하다/같다)

Korean Homonyms

Being Sick in Korea

Vocabulary

Click on the English word to see information and examples of that word in use (you probably won’t be able to understand the grammar within the sentences at this point, but it is good to see as you progress through your learning).

A PDF file neatly presenting these words and extra information can be found here.

You can try to find all of the words from this lesson, and all of the words from every lesson in Unit 1 in a package of twenty five Word Searches.

Nouns:

잠 = sleep

Common Usages:

늦잠 자다 = to sleep in

낮잠 자다 = to take a nap

잠이 들다 = to fall asleep

잠에서 깨다 = to be woken up from sleep

겨울잠 = hibernation

Notes: If you are just talking about sleeping, simply using the verb “자다” is usually appropriate. However, things related to sleep (sleeping in, waking up, falling asleep) usually use the word 잠

Examples:

저는 항상 일요일에 늦잠 자요 = I always sleep in on Sundays

저는 오늘 오후에 낮잠을 잤어요 = I took a nap in the afternoon today

저는 잠이 안 들어요 = I can’t fall asleep

모자 = hat

Common Usages:

모자를 쓰다 = to wear a hat

Examples:

우리 학교에서 모자를 쓰지 마세요 = Don’t wear a hat in our school

저의 아버지는 모자를 항상 써요 = My father always wears a hat

저는 저의 모자를 가져갈 거예요 = I will bring my hat

그 사람은 너무 큰 모자를 써요 (쓰다) = That person is wearing too big of a hat

줄 = line, string, rope, queue

Common Usages:

줄넘기 jump rope

줄에 서 있다 = to be standing in line

Examples:

줄이 왜 이렇게 길어요? = Why is the line so big?

나는 줄에 걸렸어 = I tripped over the line

감기 = a cold

Common Usages:

감기에 걸리다 = to catch a cold

Examples:

감기는 나았어요 = My cold is better

따뜻하게 안 입으면 감기에 걸릴 거예요 = If you don’t dress warm(ly), you will catch a cold

우리 애기는 어제 감기에 걸렸어요 = Our baby caught a cold yesterday

기침 = cough

Common Usages:

기침을 하다 = to cough

Examples:

그는 심하게 기침을 했어요 = He was coughing severely

저의 아들은 시끄럽게 기침했어요 = My son was coughing loudly

설사 = diarrhea

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “설싸”

Common Usages:

설사를 하다 = to have diarrhea

Example:

설사는 맛있어요 = Diarrhea is delicious

설사를 하는 것은 재미있어요 = Having diarrhea is fun

독감 = the flu

Common Usages:

독감에 걸리다 = to catch/have the flu

Example:

모든 학생들은 독감에 걸렸어요 = All the students have the flu

재채기 = sneeze

Common Usages:

재채기를 하다 = to sneeze

재채기를 참다 = to hold a sneeze

Example:

나이가 많은 사람들은 항상 재채기를 시끄럽게 해요 = Old people always sneeze loudly

동아리 = a club in school or university

Notes: It’s hard to explain exactly what this is in English – but Korean high school students are usually forced to join a club at school. These clubs are called “동아리”

Example:

저는 댄스 동아리에 들었어요 = I entered a dancing club

무슨 동아리 해? = What club are you in?

취미 = hobby

Common Usages:

취미 삼아…. 하다 = to do something as a hobby

Example:

취미가 뭐예요? = What are(is) your hobbies?

저는 취미가 없어요 = I don’t have any hobbies

수학 = math

Common Usages:

수학수업 = math class

수학문제 = math problem

수학 교과서 = math text book

Examples:

저는 수학을 못해요 = I am bad at math

저는 그 수학문제를 연필과 종이로 풀었어요 = I solved that math problem using a paper and a pencil

수학은 제가 제일 좋아하는 수업이에요 = Math is my favorite class

가족 = family

Common Usages:

우리 가족 = our family

가족용 = something intended for use for families

대가족 = big family

Examples:

저는 어제 가족을 만났어요 = I met my family yesterday

우리 가족은 일요일마다 교회를 다녀요 = Our family goes to church every Sunday

가족은 가장 중요해요 = Family is the most important

제가 미국에 있었을 때 가족을 보고 싶었어요 = When I was in the US, I missed my family

저는 여자친구를 가족한테 소개했어요 = I introduced my girlfriend to my family

실력 = skills

Common Usages:

영어실력 = English ability

한국어실력 Korean ability

실력을 늘리다 = to increase one’s ability

실력이 늘다 = for one’s ability to be increased

실력이 떨어지다 = for one’s skills to go down

Example:

그 학생은 또래보다 영어실력이 뒤처지고 있어요 = That student is falling behind his peers in English ability

저의 한국어실력은 작년보다 많이 늘었어요 = My Korean skills have gotten much better compared to last year

열심히 공부한 이래로 실력은 빨리 늘었어요 = Since studying hard, my skills have been increasing

사촌 = cousin

Notes: “사” represents that your cousins are four measures of “blood” away from you. Your uncles are one step closer, and therefore “삼” is used in the word “삼촌”

Example:

저의 사촌은 군대에 갔어요 = My cousin went to the army

삶 = life

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “삼”

Common Usages:

~삶을 살다 = to live a life of~

삶의 의미 = the meaning of life

Examples:

그는 흥미로운 삶을 살아요 = He lives an interesting life

그는 어려운 삶을 경험했어요 = He experienced a difficult life

맥주 = beer

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “맥쭈”

Common Usages:

맥주 두 병 = two bottles of beer

맥주 두 잔 = two glasses of beer

생맥주 = tap beer

Example:

맥주 한 병 주세요! = One bottle of beer, please!

한국 사람들은 맥주를 자주 마시지 않아요 = Korean people don’t drink beer often

아저씨! 맥주 한 잔 주세요! = Sir! Give me one glass of beer please!

맥주가 싫어요 = I don’t like beer

과거 = past

Notes: This can be used as an adverb to indicate something happened in the past. For example:

저는 과거에 그런 행동을 많이 했어요 = I acted like that a lot in the past

It can also be used as a noun, for example:

그의 과거는 큰 비밀이에요 = His past is a big secret

마음 = one’s heart/mind

Common Usages:

마음 대로 = as one wishes

마음에 들다 = to like something (literally, for something to go into one’s heart)

마음이 변하다 = to change one’s mind

마음에 걸리다 = to feel guilty about something (for something to be caught in one’s heart)

마음을 정하다 = to make up one’s mind

Examples:

그 사람의 마음은 따뜻해요 = That person has a warm heart

그것을 마음 대로 하세요 = Do that as you wish

저는 저 그림이 마음에 들어요 = I like that picture

그림 = picture, painting

Notes: This word isn’t used to refer to a picture that one takes with a camera. Use “사진” for that word.

Common Usages:

그림을 그리다 = to draw a picture

그림자 = shadow

Examples:

그림은 벽에 걸려 있어요 = The picture is hanging on the wall

저는 그 그림이 마음에 들어요 = I like that picture

그 그림은 높은 가치가 있어요 = That picture has a high value

그 학생은 그림을 잘 그리는 재능을 가지고 있어요 = That student has a talent for drawing (pictures)

그 그림을 볼 때 배경이 무슨 의미가 있는지 생각해 보세요 = When you look at the painting, try to think about what meaning the background has

속 = inside

Common Usages:

물속 = inside the water

뱃속 = inside a stomach/belly

꿈속에 = in one’s dream

Notes: Korean people can’t explain the difference between 안 and 속.

속 is more commonly used when, if you enter something, the place will be filled with stuff and is not “empty”. Conversely, “안” would be more commonly used when, if you enter something, the place is basically empty.

For example, if you enter water or if you enter your body. In both cases, “속” would be used to refer to the inside of a body, or the inside of water. If you enter your body, it is filled with stuff, and if you enter the water, it is still all water.

The opposite is if you are talking about a room, or a building. You can go into those places and it is relatively empty.

Example: 저는 속이 안 좋아요 = I don’t feel good (my insides aren’t good)

Verbs:

들다 = to lift, to carry, to hold

들다 follows the ㄹ irregular

Common Usages:

고개를 들다 = to raise one’s head

손을 들다 = to raise one’s hand

들어올리다 = to raise something/put it up

Notes: 들다 can be used in many different ways. “to lift/carry/hold something” is one of the main overarching usages. See below in this lesson for more information

Examples:

저는 바닥에 있는 박스를 들었어요 = I lifted the box on the floor

그는 고개를 들었어요 = He lifted his head

저는 손을 들었어요 = I raised my hand

저는 가방을 들었어요 = I carried the/my bag

들다 = to enter, to go into

들다 follows the ㄹ irregular

Notes: 들다 can be used in many different ways. “to enter, go into” is one of the main overarching usages. See below in this lesson for more information

Common Usages:

들어가다 = to go in

들어오다 = to come in

Examples:

나는 동아리에 들었어 = I joined a club

저는 잠이 들었어요 = I fell asleep (I “entered” sleep)

저는 그 그림이 마음에 들어요 = I like that picture (That picture enters my heart)

가져오다 = to bring an object

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “가저오다”

This is not used when you “bring” a person somewhere. Instead, the word “데려오다” is used

가져오다 often translates to “to bring” and 가져가다 often translates to “to take.” However, the translation of “to bring” could work for both 가져오다 and 가져가다.

가지다 means “to possess” and “오다” and “가다” mean “to come” and “to go” respectively. Deciding to use 가져오다 or 가져가다 depends on the point of reference of the acting agent in the sentence to the speaker. Specifically, whether the acting agent is coming or going to the location in question.

Imagine you have money at your house, and you will go to your friend’s house later to give it to him. Therefore, you will have to “bring” or “take” (same meaning) that money with you when you head over there. If you are currently at your house and are talking to your friend about what you will do, you should use the word “가져가다” because you are going to your friend’s house while in possession of the money (저는 돈을 가져갈 거예요). In this example, 가져가다 is used and the best English translation would be “I will bring the money.”

However, imagine you have already arrived at your friend’s house with the money. You can use the word “가져오다” because you came to your friend’s house while in possession of the money (저는 돈을 가져왔어요). In this example, 가져오다 is used and the best English translation would be “I brought the money.”

People would read those two examples and think “Oh, so if it is something happening in the future – I should use 가져가다 and if it is something happening in the past, I should use 가져오다.”

No. It has nothing to do with the tense of the sentence. It has everything to do with the point of reference of the acting agent of the sentence to the speaker.

For example, imagine you are at your house with the money. If your friend wants to tell you to “bring the money,” he should use the word “가져오다” because you are coming (not going) to him. To his reference, you are “coming.” In this case, 가져오다 should be used.

Examples:

저는 저의 숙제를 가져왔어요 = I brought my homework

저는 지갑을 안 가져왔어요 = I didn’t bring my wallet

저는 친구가 사과를 가져오는 것을 원해요 = I want my friend to bring apples

비가 올 까봐 우산을 가져왔어요 = I brought an umbrella because I was worried that it was going to rain

가져가다 = to bring/take an object

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “가저가다”

This is not used when you “take” a person somewhere. Instead, the word “데려가다” is used

가져오다 often translates to “to bring” and 가져가다 often translates to “to take.” However, the translation of “to bring” could work for both 가져오다 and 가져가다.

가지다 means “to possess” and “오다” and “가다” mean “to come” and “to go” respectively. Deciding to use 가져오다 or 가져가다 depends on the point of reference of the acting agent in the sentence to the speaker. Specifically, whether the acting agent is coming or going to the location in question.

Imagine you have money at your house, and you will go to your friend’s house later to give it to him. Therefore, you will have to “bring” or “take” (same meaning) that money with you when you head over there. If you are currently at your house and are talking to your friend about what you will do, you should use the word “가져가다” because you are going to your friend’s house while in possession of the money (저는 돈을 가져갈 거예요). In this example, 가져가다 is used and the best English translation would be “I will bring the money.”

However, imagine you have already arrived at your friend’s house with the money. You can use the word “가져오다” because you came to your friend’s house while in possession of the money (저는 돈을 가져왔어요). In this example, 가져오다 is used and the best English translation would be “I brought the money.”

People would read those two examples and think “Oh, so if it is something happening in the future – I should use 가져가다 and if it is something happening in the past, I should use 가져오다.”

No. It has nothing to do with the tense of the sentence. It has everything to do with the point of reference of the acting agent of the sentence to the speaker.

For example, imagine you are at your house with the money. If your friend wants to tell you to “bring the money,” he should use the word “가져오다” because you are coming (not going) to him. To his reference, you are “coming.” In this case, 가져오다 should be used.

Examples:

얼마나 많은 돈을 가져갈 거예요? = How much money will you bring/take?

날씨가 너무 더울 것이기 때문에 반바지를 가져갈 거예요 = I am going to bring/take shorts because the weather will be hot

돌리다 = to turn, to run a machine, to hand out

This word appears in Korean Sign Explanation Video 14.

Common Usages:

세탁기를 돌리다 = to turn on, use a washing machine

기계를 돌리다 = to use a machine

A를 돌리다 = to distribute something

Examples:

저는 밤에 세탁기를 돌렸어요 = I ran my laundry machine at night

저는 친구들에게 선물을 돌렸어요 = I distributed/handed out presents to my friends

돌다 = to turn oneself, to rotate oneself

돌다 follows the ㄹ irregular

Common Usages:

돌아가다 = to go back

돌아오다 = to come back

Notes: 돌리다 is used when one turns an object. 돌다 can be used when one turns his/her body.

Examples:

캐나다에 언제 돌아올 거예요? = When are you coming back to Canada?

우리는 사거리에서 왼쪽으로 돌았어요 = We turned left at the intersection

돌아보다 = to look back

Notes: A compound verb made up of “돌다” and “보다”

Example:

저는 그녀를 돌아봤어요 = I looked back at her

돌아가다 = to go back, to return

Notes: A compound verb made up of “돌다” and “가다.” If you are currently in a place and are talking about returning to another place. For example, if you are from Canada but currently in Korea and talking about returning to Canada (i.e. going back to Canada), you should use this word instead of “돌아오다.”

Common Usages:

돌아가시다 = A formal way to say somebody has “passed away” (the honorific ~(으)시 is introduced in Lesson 39)

Examples:

저는 언젠가 고향에 돌아가고 싶어요 = I want to go back to my hometown some day

저는 9월1일에 캐나다에 돌아갈 거예요 = I will go back to Canada on September 1st

무슨 일이 벌어지든지 간에 제가 집에 돌아가야 돼요 = Regardless of what happens, I need to go back/return home

돌아오다 = to come back, to return

Notes: A compound verb made up of “돌다” and “오다.” If you are currently in a place and are talking about returning to the same place. For example, if you are from Canada talking about returning to Canada (i.e. coming back to Canada), you should use this word instead of “돌아가다.”

Examples:

캐나다에 언제 돌아올 거예요? = When are you coming back to Canada?

학생들은 다음 주에 학교에 돌아와요 = The students return to school next week

경찰관들은 경찰서에 돌아왔어요 = The police officers returned to the police station

거기에 가서 돈을 갖고 돌아오세요! = Go over there, get the money and then come back!

모든 선생님들은 지금 회의 중이니 20분 후에 돌아오면 돼= All the teachers are in a meeting now, so come back in 20 minutes

돌려주다 = to give back

Notes: A compound verb made up of “돌리다” and “주다”

Example:

저는 친구에게 책을 돌려줬어요 = I gave my friend back his book

걸다 = to hang

걸다 follows the ㄹ irregular

Common Usages:

시동을 걸다 = to start the engine of your car

Example:

저는 사진을 벽에 걸었어요 = I hung a picture on the wall

주문하다 = to order

Common Usages:

주문을 받다 = to receive an order

주문을 취소하다 = to cancel an order

Examples:

저기요! 지금 주문할게요! = Excuse me! We would like to order now!

음료수를 주문할래요? = Shall we order some drinks?

지금 주문해도 돼요? = Can we/I order now?

결혼하다 = to get married

The noun form of this word translates to “marriage”

Examples:

그녀는 아직 결혼하지 않았어요 = She still hasn’t gotten married yet

그 부부는 50년 전에 결혼했어요 = That couple got married 50 years ago

우리는 올해 결혼하고 싶어요 = We want to get married this year

우리는 결혼식의 날짜를 아직 안 정했어요 = We still haven’t set a date for the wedding

부르다 = to call out

부르다 follows the 르 irregular

Notes: When used to say that one “calls” something by a certain name, “라고” is usually used in the sentence. See Lesson 52 for more information.

Examples:

저는 저의 여자 친구를 ‘애기’라고 불러요 = I call my girlfriend “baby”

저는 그의 이름을 불렀어요 = I called his name

저는 저의 누나를 불렀어요 = I called my sister

고르다 = to choose, to pick

고르다 follows the 르 irregular

Example:

저는 이것과 저젓 중에 고를 수 없어요 = I can’t choose between the two

우리는 맛있는 고기를 골라서 같이 먹었어요 = We chose delicious meat then ate together

저는 두 번째 남자를 골랐어요 = I chose the second man

넣다 = to insert, to put inside

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “너타”

Examples:

저는 야채를 냉장고에 넣었어요 = I put the vegetables in the fridge

저는 핸드폰을 상자에 넣었어요 = I put the phone in the box

케이크 반죽에 밀가루를 넣으세요 = Put some flour into the cake batter, please

경험하다 = to experience

Example:

그는 어려운 삶을 경험했어요 = He experienced a difficult life

그 학교에서 일한 것은 좋은 경험이었어요 = Working at that school was good experience

제가 여기서 일하고 싶은 이유는 새로운 경험을 하고 싶기 때문이에요 = The reason I want to work here is because I want to have a new experience

설명하다 = to explain

The noun form of this word translates to “an explanation”

Example:

저는 어려운 내용을 천천히 설명했어요 = I explained the difficult content slowly

저는 선생님에게 숙제에 대한 설명을 요청했어요 = I asked the teacher for an explanation of the homework

저는 학생들한테 그것을 간단히 설명했어요 = I explained it simply to the students

자랑하다 = to show off

Notes: 자랑스럽다 translates to “to be proud”

Example:

자랑하지 마세요! = Don’t show off!

제 친구는 부자인 아버지를 자랑했어요 = My friend boasted about/was showing off his rich father

Passive verbs:

걸리다 = to be hanging

Notes: 걸리다 has many meanings. See below in this lesson for more information.

Example:

그림은 벽에 걸려 있어요 = The picture is hanging on the wall

걸리다 = to be caught, to be stuck, to be trapped

Example:

나는 줄에 걸렸어 = I tripped over the line

걸리다 = to catch a cold/sickness

Common Usages:

감기에 걸리다 = to catch a cold

독감에 걸리다 = to catch the flu

Example:

저는 감기에 걸렸어요 = I caught a cold/I have a cold

모든 학생들은 감기에 걸렸어요 = All the students have a cold

걸리다 = to “take” a certain amount of time

Common Usages:

한 시간 걸리다 = to take one hour

Example:

서울부터 인천까지 두 시간 걸려요 = It takes two hours to get from Seoul to Incheon

우리 학교에서 식당까지 10분 걸려요 = It takes 10 minutes to get from our school to the restaurant

Adjectives:

똑같다 = to be exactly the same

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “똑깓다”

Notes: When comparing two things by saying they are the same, it is more common to use 똑같다 instead of 같다. For example, instead of saying:

저와 저의 형은 같아요

It would be more natural to say:

저와 저의 형은 똑같아요

See below in this lesson for more information

Example:

우리가 똑같은 옷을 입고 있어요 = We are wearing exactly the same clothes

미국은 캐나다와 거의 똑같아요 = The US is almost the same as Canada

자랑스럽다 = to be proud

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “자랑스럽따”

자랑스럽다 follows the ㅂ irregular

Notes: 자랑스럽다 is an adjective. To indicate that you are proud of something/somebody, the particle ~이/가 must be attached to the object of the sentence. See Lesson 15 for more information.

Example:

저는 우리 아들이 자랑스러워요 = I am proud of our son

나는 네가 자랑스러워 = I am proud of you

저는 저의 딸이 아주 자랑스러워요 = I am very proud of my daughter

저는 학생들이 자랑스러워요 = I am proud of the students

또 다르다 = another

Notes: The function of “또 다르다” is hard to explain, but it is easier to explain (and understand) if you think of it as two separate words (which it actually is). It is a combination of the adjective “다르다” and the adverb “또”, which is used when something happens again.

“또 다르다” is used when one particular thing has already been described, and you are explaining another thing. For example, imagine you are sitting in a meeting with your coworkers discussing potential problems for a plan. People are all discussing the problems they see, and you can point out:

또 다른 문제는 그것이 비싸요 = Another problem is it (that thing) is expensive

In this same respect, you can say the following sentence, and although the translation in English is similar, try to understand the difference in adding “또”:

저는 또 다른 영화를 봤어요 = I saw ANother movie

In this, maybe the person saw one movie, and then again saw a different movie.

시끄럽다 = to be noisy, to be loud

The pronunciation of this word is closer to “시끄럽따”

시끄럽다 follows the ㅂ irregular

Common Usages:

시끄러운 학생 = loud students

시끄러운 음악 = loud music

시끄럽게 말하다 = to speak loudly

Common Usages: 시끄럽게 (loudly)

Example:

학생들은 시끄럽게 공부했어요 = The students studied loudly

시끄러워서 미안해요 = Sorry it is so loud!

여기가 너무 시끄러워서 저는 집중할 수 없어요 = I can’t concentrate here because it is too loud

영화를 보는 동안 다른 사람들이 너무 시끄러웠어요 = While watching the movie, the other people were really loud

학생들이 너무 시끄러워서 저는 교수님의 말을 못 들었어요 = The students were too loud, so I couldn’t hear the professor

흔하다 = to be common

Common Usages:

흔하지 않다 = uncommon

Example:

덕석은 흔하지 않은 이름이에요 = “덕석” is not a common name

드물다 = to be rare

드물다 follows the ㄹ irregular

Common Usages:

드문 현상 = a rare phenomenon

Example:

그 그림은 매우 드물어요 = That painting is really rare

Adverbs and Other words:

아마도 = maybe/might

Example:

아마도 우리가 내일 갈 거예요 = Maybe we will go tomorrow

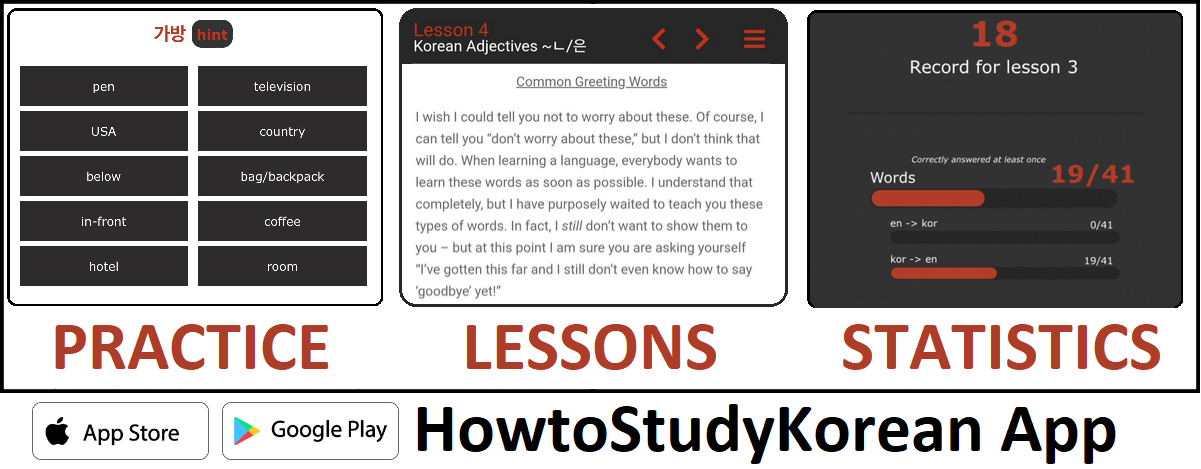

For help memorizing these words, try using our mobile app.

You might also want to try listening to all of the words on loop with this Vocabulary Practice video.

There are 1050 vocabulary entries in Unit 1. All entries are linked to an audio file.

You can download all of these files in one package here.

Introduction

This lesson will have a very different feel than all the previous lessons you have learned. Most of the words you have learned so far can be understood and used in sentences without much thought or hesitation. For example, if you knew how to say this:

저는 한국어를 배웠어요 = I learned Korean

And then subsequently learned “공부하다” (to study), it would be easy to figure out that you could also say:

저는 한국어를 공부했어요 = I studied Korean.

However, there are many words that you would not be able to pick up instinctively because they follow different rules or patterns. In this lesson, I want to teach you about some of these words. I also want to use this lesson as a means to teach you some small concepts in Korean that you should know. These concepts are important, but are too small to have an entire lesson dedicated to that one concept. So, I have included them in this “miscellaneous” lesson:

More about 좋다/싫다 to 좋아하다/싫어하다

I have told you a few times that in most words ending in 하다, you can remove the ~하다 and the remaining word then becomes a noun of that verb. For example:

말 = speech/words/the thing that you say

말하다 = to speak

주문 = an order

주문하다 = to order

결혼 = marriage

결혼하다 = to marry

존경 = respect

존경하다 = to respect

This cannot be done with 좋아하다 and 싫어하다. That is:

좋아 is not a noun that means “likeness” (or whatever), and

싫어 is not a noun that means “dis-likeness “(or whatever)

Note, however that 좋아 and 싫어 can be found in sentences, but only as conjugated forms of 좋다/싫다 and not as the noun form of 좋아하다 and 싫어하다. You learned in previous lessons that 좋다 and 싫다 are adjectives. As adjectives, they can describe an upcoming noun or predicate a sentence. For example:

저는 좋은 김치를 먹었어요 = I ate good kimchi

김치는 좋아요 = Kimchi is good

Just a quick note. Only in rare cases would you actually say ‘김치는 좋아요.’ In most cases if you wanted to describe 김치 by saying it was good, you would use the word 맛있다 instead. You would only really use this sentence if you/somebody was talking about something bad (like maybe something bad for your health), and then you could say “… is bad, but Kimchi is good.” Nonetheless, it is grammatically correct, and I am specifically using this sentence to make a point that you will understand later in the lesson.

좋아하다 is made by adding ~아/어하다 to the stem of 좋다. This changes 좋다 from an adjective (good) to a verb (to like). Likewise,

싫어하다 is made by adding ~아/어하다 to the stem of 싫다. This changes 싫다 from an adjective (not good) to a verb (to dislike).

It would be good to note that you can add ~아/어하다 with some other adjectives as well. 좋다 and 싫다 are the most common (and the most important) to worry about right now, but other common examples are:

부끄럽다 = shy (this is an adjective)

부끄러워하다 = shy (this is a verb)

부럽다 = envious (this is an adjective)

부러워하다 = envious (this is a verb)

Aside from knowing that one is a verb and one is an adjective, you don’t need to worry about these other words right now. I talk more about this concept and how they are used differently, but not until much later in Lesson 105. For now, let’s just focus on 좋아하다 and 싫어하다.

As a verb, 좋아하다 can be used to indicate that one “likes” something. For example:

김치는 좋아요 = Kimchi is good

저는 김치를 좋아해요 = I like Kimchi

Likewise, 싫어하다 can be used to indicate that one “dislikes” something. For example:

김치는 싫어요 = Kimchi is bad/not good

저는 김치를 싫어해요 = I don’t like Kimchi

However, the use of “좋다” and “싫다” in these sentences is commonly used to say:

김치가 좋아요 = I like Kimchi

김치가 싫어요 = I don’t like Kimchi

Or, other examples:

학교가 좋아요 = I like school

학교가 싫어요 = I don’t like school

맥주가 좋아요 = I like beer

맥주가 싫어요 = I don’t like beer

The mechanics to how this is done is talked about next.

Subject – Object – Adjective Form

One of the basic fundamentals of grammar (not just Korean grammar) is that an adjective cannot act on an object. This means in Korean you can never have a sentence predicated by an adjective that is acting on a word with the object particle ~를/을. This means that you cannot say this:

저는 김치를 좋다 = I kimchi good

(this doesn’t make sense in either language)

But, you can say any of these:

저는 김치를 먹었어요 = I ate kimchi

An object predicated by a verb

김치가 좋아요 = kimchi is good

A subject predicated by an adjective

저는 좋은 김치를 먹었어요 = I ate good kimchi

An object being described by an adjective predicated by a verb

That being said, sometimes, Korean people actually DO make sentences that are predicated by adjectives and also have an “object.” Remember though, you cannot (100% cannot) use an adjective to act on an object. So how do Korean people say this? They do so by adding ~이/가 to the object instead of ~을/를. This technically makes the grammar within the sentence correct because there is not an adjective acting on an object. Take a look at the example:

김치는 좋아요 = Kimchi is good

저는 김치를 좋아해요 = I like kimchi, which can also be said like this

저는 김치가 좋아요 = I like kimchi

What I am trying to get at here – is that often times in Korean there is an adjective or passive verb that acts on objects. However, these adjective/passive verbs must (of course) always be treated as an adjective or passive verb.

Adjectives and passive verbs can never act on objects, so instead of using ~를/을 in these situations, you have to use ~이/가. Another example where this is commonly done is with 그립다:

그립다 = this word is translated as “to miss,” but is usually used when talking about missing a non-person (it is sometimes used to say that you miss a person, but we will talk about how to say you miss a person in Lesson 17).

그립다 is an adjective in Korean (because it actually describes the feeling rather than an action verb). This means that if you want to say “I miss Korean food” you cannot say:

저는 한국 음식을 그리워요. Instead, you must say:

저는 한국 음식이 그리워요 = I miss Korean food

More examples. Notice that the predicating word of each sentence in an adjective:

나는 네가 자랑스러워 = I am proud of you

나는 그 사람이 싫어 = I don’t like that person

저는 한국이 좋아요 = I like Korea

You also saw this same phenomenon in the previous lesson with passive verbs. Remember, you cannot have a passive verb act on an object. Therefore, we saw the following types of examples in the previous lesson:

저는 그것이 기억나요! = I remember that!

저는 땀이 나요! = I’m sweating!

저는 화가 났어요 = I was/I am angry

Korean Word: 들다

The word 들다 in Korean is very difficult because it can be used in so many ways. Two of the most common usages are:

들다 = to carry/hold something

들다 = to enter/go into something/somewhere

Both of these usages are overarching situations that most of the usages of 들다 can fit into. The difficulty with 들다 is, because it can be used in so many different ways, it is often hard to come up with a translation that fits all possible situations. Let me show you three examples of how 들다 can be used under the overarching situation of “to enter/go into something/somewhere.”

나는 동아리에 들었어 = I joined a club (I “entered” a club)

(나는) 잠이 들었다 = I fell asleep (I “entered” sleep)

저는 그 그림이 마음에 들어요 = I like that picture (That picture enters my heart)

The definition of the word 마음 generally refers to one’s heart/one’s mind

Now, let me show you examples of how 들다 can be used under the overarching situation of “to carry/hold something.”

저는 손을 들었어요 = I raised my hand (I “held up” my hand/carried my hand)

저는 가방을 들었어요 = I carried the/my bag

Okay, so what’s my point?

Well, I have three points actually.

1) First, I wanted to introduce how 들다 can be used. With a general understanding of the two overarching usages presented here (along with the specific situations outlined in the example sentences), you should be able to tackle most usages of 들다 as you continue to study more advanced sentences.

2) This is really crucial to your development of Korean and how it relates to the meanings you have of words from your understanding of English. You have to realize that Korean and English are fundamentally different, and it is very difficult to translate sentences sometimes. In cases like these, you should try not to translate the meaning of a word directly into a specific definition. Rather, you should be open to the fact that it can have many meanings depending on the context.

For example, imagine if you knew the following words and their definitions:

- 저 = I/me

- 마음 = heart/mind

- 들다 = enter

- 그림 = picture

And you saw the following sentence:

Would you be able to understand its meaning if I had not explained it to you earlier? Many learners of Korean might read that and say “Well, it looks like that person has a picture entering his heart/mind… but I’m not quite sure what that means.”

This is the first of many times where I will encourage you to not translate/understand sentences literally. Instead, try to understand what the meaning of a sentence could be based on your understanding of the words within it. For example, if you come across the word “들다” in your studies, realize that it can have many usages – and just because it doesn’t immediately look like it will translate to “enter” or “carry,” an open mind might allow you to see things in different ways.

3) I specifically wanted to teach you the meaning of 들다 because it is commonly used in compound words, which I will talk about in the next section.

Korean Compound Verbs

You will notice (or may have already noticed) that many Korean verbs are made by combining two verbs together. This is usually done by adding one verb to the stem of the other, along with ~아/어. When this happens, the meanings of both of the words form to make one word. For example:

들다 = to enter something

가다 = to go

들다 + 가다 = 들 + 어 + 가다

= 들어가다 = to go into something

아버지는 은행에 들어갔어요 = My dad went into the bank

들다 = to enter something

오다 = to come

들다 + 오다 = 들 + 어 + 오다

= 들어오다 = to come into something

남자는 방에 들어왔어요 = A man came into the room

나다 = to arise out of something/come up/come out

가다 = to go

나다 + 가다 = 나 + 아 + 가다

= 나가다 = to go out of something

저는 집에서 나갔어요 = I went out of home (I left home)

나다 = to arise out of something/come up/come out

오다 = to come

나다 + 오다 = 나 + 아 + 오다

= 나오다 = to come out of something

학생은 학교에서 나왔어요 = The student came out of school

가지다 = to own/have/posses

오다 = to come

가지다 + 오다 = 가지 + 어 + 오다

= 가져오다 = to bring something

나는 나의 숙제를 가져왔어 = I brought my homework

그 학생은 숙제를 가져오지 않았어 = That student didn’t bring his homework

가지다 = to own/have/posses

가다 = to go

가지다 + 가다 = 가지 + 어 + 가다

= 가져가다 = to take something

저는 저의 모자를 가져갈 거예요 = I will bring/take my hat

가져오다 often translates to “to bring” and 가져가다 often translates to “to take.” However, the translation of “to bring” could work for both 가져오다 and 가져가다.

가지다 means “to possess” and “오다” and “가다” mean “to come” and “to go” respectively. Deciding to use 가져오다 or 가져가다 depends on the point of reference of the acting agent in the sentence to the speaker. Specifically, whether the acting agent is coming or going to the location in question.

Imagine you have money at your house, and you will go to your friend’s house later to give it to him. Therefore, you will have to “bring” or “take” (same meaning) that money with you when you head over there. If you are currently at your house and are talking to your friend about what you will do, you should use the word “가져가다” because you are going to your friend’s house while in possession of the money (저는 돈을 가져갈 거예요). In this example, 가져가다 is used and the best English translation would be “I will bring the money.”

However, imagine you have already arrived at your friend’s house with the money. You can use the word “가져오다” because you came to your friend’s house while in possession of the money (저는 돈을 가져왔어요). In this example, 가져오다 is used and the best English translation would be “I brought the money.”

People would read those two examples and think “Oh, so if it is something happening in the future – I should use 가져가다 and if it is something happening in the past, I should use 가져오다.”

No. It has nothing to do with the tense of the sentence. It has everything to do with the point of reference of the acting agent of the sentence to the speaker.

For example, imagine you are at your house with the money. If your friend wants to tell you to “bring the money,” he should use the word “가져오다” because you are coming (not going) to him. To his reference, you are “coming.” In this case, 가져오다 should be used.

You will come across many of these words when you are learning how to speak Korean. It is not something terribly difficult, but is something that you should be aware of (it helps to understand the word if you realize that it is made up of two separate words).

Another word that you will see commonly in these compound words is “돌다”:

돌다 = to turn/to spin/to rotate

Examples of compound words:

돌다 + 보다 = 돌아보다 = to turn around (and see)

돌다 + 가다 = 돌아가다 = to return/go back

돌다 + 오다 = 돌아오다 = to return/come back

돌리다 + 주다 = 돌려주다 = to give back

저는 9월1일에 캐나다에 돌아갈 거예요 = I will go back to Canada on September 1st

저는 친구에게 책을 돌려줬어요 = I gave my friend back his book

That’s good enough for now, but you will continue to see these as you progress through your studies.

Different/Similar/Same in Korean (다르다/비슷하다/같다)

Three words that you have learned in previous lessons are:

다르다 = different

비슷하다 = similar

같다 = same

Using these words isn’t as straight forward as it would seem, so I wanted to spend some time teaching you how to deal with them. Of course, in simple sentences, they can be used just like any other adjectives. For example:

그것은 비슷해요 = That is similar

우리는 매우 달라요 = We are so different

우리는 같아요 = We are the same

The sentence above sounds unnatural in Korean. Although “같다” translates to “the same,” in most cases (especially in cases like this where nothing is being compared), it is more natural to use the word “똑같다,” which usually translates to “exactly the same.”

For example:

우리는 똑같아요 = We are exactly the same

When comparing things like this in English, we use a different preposition for each word. For example:

I am similar to my friend

That building is different from yesterday

Canadian people are the same as Korean people

In Korean, the particle ~와/과/랑/이랑/하고 can be used to represent all of these meanings. For example:

저는 친구와 비슷해요 = I am similar to my friend

그 건물은 어제와 달라요 = That building is different from yesterday

캐나다 사람들은 한국 사람들과 같아요 = Canadian people are the same as Korean people

이 학교는 우리 학교와 똑같아요 = This school is exactly the same as our school

The ability of ~와/과/랑/이랑/하고 to be used in all of these cases creates confusion for Korean people when they learn English. You will often hear mistakes from Korean people like:

“This school is the same to our school”

Notice in the sentence above that the particle ~와/과/랑/이랑/하고 is used to denote that something is different from, similar to, or the same as something else. In theory, you could change the order of the sentences (to make the sentence structure similar to what you learned in Lesson 13) to indicate that two things (this and that) are different, similar or the same. For example:

우리 학교와 이 학교는 똑같아요 = Our school and this school are exactly the same

As you can see with the English translation – this doesn’t create any difference in meaning. It merely changes the wording of the sentences and the function of the particles slightly.

I talk about the usage of 같다 later in Lessons 35 and 36. Specifically, in Lesson 36 I talk about how 같다 is more commonly used to say “something is like something.” I don’t want to get into this too much in this lesson, because the purpose of this section was for me to introduce you to the grammar within these sentences so you could apply it to what I am about to introduce next.

Check this grammar out. This is probably an easy sentence to you now:

나는 잘생긴 남자를 만났어 = I met a handsome man

Subject – adjective (describing an) – object – verb

What about these next sentences?

나는 비슷한 남자를 만났어 = I met a similar man, or

나는 같은 남자를 만났어 = I met the same man

These sentences have the same structure as before:

Subject – adjective (describing an) – object – verb

That should be easy for you too. But what about if you wanted to say “I met a man who is similar to your boyfriend.” Seems too complicated, but let’s break it down:

너의 남자친구와 비슷하다 = similar to your boyfriend

비슷하다 is an adjective – which means it can modify a noun:

비슷한 남자 = similar man

너의 남자친구와 비슷한 남자 = A man (that is) similar to your boyfriend

나는 ( — )를 만났어 = I met —

나는 (너의 남자친구와 비슷한 남자)를 만났어 = I met a man that is similar to your boyfriend

This structure is very complex and is an introduction to describing nouns with phrases instead of simply using one adjective. In Lesson 26, you will learn more about how to describe nouns with things other than simple adjectives – such as verbs and complex phrases.

The meaning of “different” in English has more than one nuance, which are possessed by “다르다” as well. Although the meaning of “different” in the two sentences below is similar, try to see that they are slightly different:

I am different than him

I saw a different movie

The first one describes that something is not the same as something else.

The second one has a meaning similar to “other” or “another,” where (in this case) the person did not see the movie that was originally planned, but instead saw “another” or a “different” movie.

다르다 can be used in both situations. For example:

저는 그와 달라요 = I am different from him

저는 다른 영화를 봤어요 = I saw a different (another) movie

“또 다르다” usually translates to “another,” while “다르다” translates to “other.” However, in the example above, replacing “another” with “other” makes it sound weird.

The function of “또 다르다” is hard to explain, but it is easier to explain (and understand) if you think of it as two separate words (which it actually is). It is a combination of the adjective “다르다” and the adverb “또”, which is used when something happens again.

“또 다르다” is used when one particular thing has already been described, and you are explaining another thing. For example, imagine you are sitting in a meeting with your coworkers discussing potential problems for a plan. People are all discussing the problems they see, and you can point out:

또 다른 문제는 그것이 비싸요 = Another problem is it (that thing) is expensive

In this same respect, you can say the following sentence, and although the translation in English is similar, try to understand the difference in adding “또”:

저는 또 다른 영화를 봤어요 = I saw ANother movie

In this, maybe the person saw one movie, and then again saw a different movie.

Words that are the same but have different meanings (Korean Homonyms)

This may be something that is obvious when learning any language, but I wanted to point it out. In Korean, there are a lot of words that have more than one meaning. It is like this in English as well, but most people never notice it until they stop to think about how many there actually are. Whenever there is a word with many meanings in Korean, these different meanings will always have a separate entry in our vocabulary lists (not necessarily in the same lesson, however). An example of this is “쓰다”:

쓰다 = to write

쓰다 = to use

쓰다 = to wear a hat

Each of these words has had a separate entry in our vocabulary lists. However, when a word has many meanings, but most of those meanings can be combined into a few ‘umbrella term’ meanings – only those ‘umbrella term’ meanings will be shown. A good example we talked about earlier is 들다. 들다 has so many meanings, most of which can fit into three or four broad definitions.

Either way, be aware that many words have many meanings in Korean:

나는 편지를 친구를 위해 쓸 거야 = I am going to write a letter for my friend

나는 그 기계를 썼어 = I used that machine

저의 아버지는 모자를 항상 써요 = My father always wears a hat

Another word that has many common meanings is 걸리다:

걸리다 = to be (in the state of) hanging

걸리다 = to be caught/stuck/trapped

걸리다 = to “take” a certain amount of time

걸리다 = to catch a cold/sickness

There are more usages, but lets just focus on these four for now:

걸리다 = to be hanging

Similar to the passive verbs you learned in the previous lesson, this verb can be used to indicate the passive ‘state’ of hanging:

그림은 벽에 걸려 있어요 = The picture is hanging on the wall

걸리다 = to be caught/stuck/trapped

A verb that can be used when something trips/gets caught/gets trapped:

나는 줄에 걸렸어 = I tripped over the line

걸리다 = to “take” a certain amount of time

This is a very useful form that we will talk about in greater detail in a later lesson. You can use this to indicate how long it takes to get from one place to another:

서울부터 인천까지 2시간 걸려요 = It takes 2 hours to get from Seoul to Incheon

우리 학교에서 식당까지 10분 걸려요 = It takes 10 minutes to get from our school to the restaurant

Notice however, that even though each of these has a very different meaning in English (to be hanging, to be caught, to take a certain amount of time) they are actually pretty similar. When a picture is ‘hanging’ on the wall, technically it is ‘stuck/trapped’ on the wall. Similarly, if you go from Incheon to Seoul, the time it takes (2 hours) is ‘stuck/trapped.’ Haha, No? Well, that’s just the way I explained it to myself when I first learned some of these words.

Try to think outside of the English box. One word in Korean is often used to represent many words in English. Usually these words aren’t actually very different, but the different translations lead us to believe that they are in fact very different. Read these sentences again and see if you can understand them this way:

The picture is caught on the wall

I was caught over the line

2 hours are caught to get from Seoul to Incheon

Obviously not natural in English – but you can probably understand what these sentences mean.

My point? Just because it looks like a word has many meanings doesn’t necessarily mean that those meanings are vastly different from each other. Think about the example from earlier in this lesson (들다) one more time. 들다 has many meanings – but most of which can be grouped into only 2 or 3 different meanings. Always keep this in mind.

Being Sick in Korea

One of the things people often try to learn first when learning a new language is how to express themselves in the event that they have to go to the doctor. This is something that wouldn’t fit into any specific lesson, so I want to cover it here:

You already know the word 아프다, which you can use to indicate that you are sick OR sore in some place. In English “sore” and “sick” mean slightly different things. Because of this, Korean people (who are learning English) often mistakenly say “My arm is sick.” Also note that 아프다 is an adjective… and for some reason ‘이/가’ are used instead of 는/은when creating sentences about a place on your body:

배가 아파요 = My stomach is sore

팔이 아파요 = My arm is sore

저는 어제 너무 아팠어요 = I was very sick yesterday

Also, you can use the word 걸리다 to indicate that you have some sort of disease/sickness. You learned a little bit about 걸리다 in the previous section. This usage of 걸리다 essentially has the same meaning that was described in all the other examples of 걸리다 (I am caught in a sickness). Korean people use this in the following way:

저는 감기에 걸렸어요 = I caught a cold/I have a cold

저는 독감에 걸렸어요 = I caught the flu/I have the flu

Notice how “에” is used in these sentences due to 걸리다 having the nuance of being stuck IN something

Also note that even though you have a cold in the present tense, Korean people use the past “걸렸다” to express that they currently have a cold.

기침 (a cough) and 재채기 (a sneeze), although not originally nouns of Chinese origin, are both nouns where you can add 하다 to get the respective verb form (to cough and to sneeze). For example:

저의 아들은 시끄럽게 기침했어요 = My son coughed loudly

(Probably more naturally translated to “My son was coughing loudly.” Korean people don’t really distinguish between simple and progressive past tenses as much as we do in English. You will learn about the progressive tense in Lesson 18.)

Wow that’s a long lesson. I have to apologize for writing these lessons so long. This lesson could have easily been broken into 2, 3 or even 4 separate lessons, but I chose against doing it that way. When I was first learning Korean, I wanted to plow through material as fast as I possibly could – and I guess that is coming out as I am writing these lessons as well.

Okay, I got it! Take me to the next lesson! Or,

Click here for a workbook to go along with this lesson.

That’s it for this lesson!

There are 1250 example sentences in Unit 1.

All entries are linked to an audio file. You can download all of these files in one package here.

Want to try to create some sentences using the vocabulary and grammar from this lesson?

Want to try to create some sentences using the vocabulary and grammar from this lesson?

This YouTube video will prompt you to translate English sentences into Korean using the concepts from this lesson.

Want to practice your listening skills?

Want to practice your listening skills?

This YouTube video will prompt you with Korean sentences to dictate using the concepts from this lesson.